To suggest gold is a controversial asset is not bold. For those watching long term, you know gold rose over 300% in the last decade before it even gained mainstream attention, let alone acceptance by many as an investment vehicle. Gold has been a medium of economic exchange for centuries across all geographies on planet Earth. This “function” blurred meaningfully following the closure of the gold window in the US by Nixon in the early 1970’s. So which is the proper time frame to judge the legitimacy and “function” of gold, including its function as an investment – centuries of human economic history or what has transpired over the last forty years?

Investors are usually most concerned with what is occurring in markets right now – today, this week, this month, this year. For many caught in the institutional performance rat race, there often is no tomorrow, only today. Short attention span theater is the norm. And when it comes to gold as an investment, today, this week, this month and this year have not been too heartwarming as price has corrected meaningfully after 12 straight up years based on annual closing prices. For those in the gold bull camp, there must be at least some tearing given unlimited money printing by the globe’s largest central banks. Should this not have been the Promised Land for the long term gold bulls as keynote currencies globally are openly and actively being debased? Gold aficionados could not have asked for a script any better than what is playing out right before our eyes! So what’s wrong with gold?

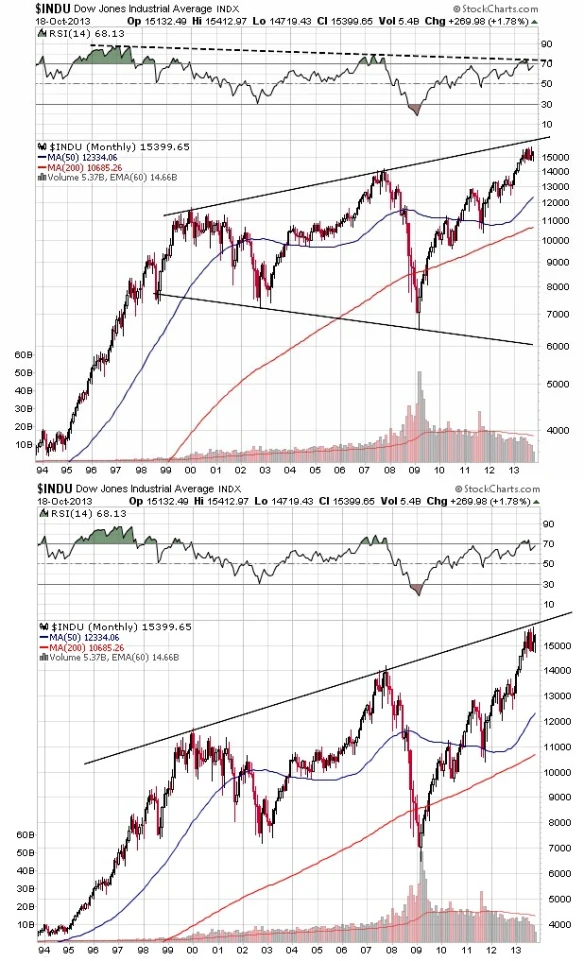

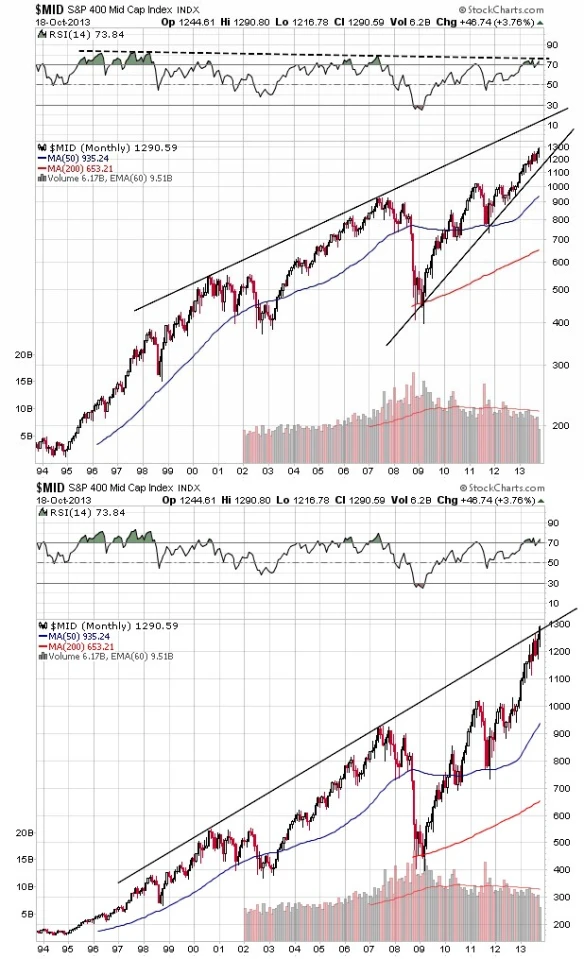

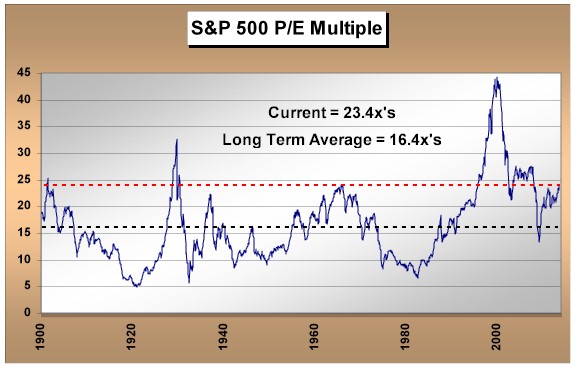

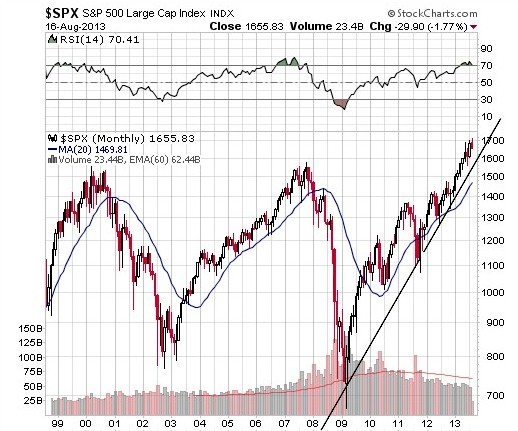

We must remember that investors as a crowd can be a very fickle bunch, especially over the short term. Investment attention shifts also between various investment drivers. For example, most often investors focus on company specific earnings when it comes to setting equity prices. But we know that lately in the US market, earnings and macroeconomic fundamentals are not the keynote drivers of equity prices. Rather, as I’ve written this year, the weight and movement of global capital have been the key drivers of this year’s investment outcomes. I believe the central bankers have finally gone too far setting global capital in motion, and thus scared Yen and Euro capital are migrating to the perceived safety that is the US dollar and US equities. This migration is supporting prices in the absence of meaningful earnings and/or revenue advances. This isn’t right or wrong, but worth remembering since no one metric drives asset prices at all times. And such is also the case with gold.

Some investors have purchased gold believing the US and the globe must return to some type of a monetary gold standard in response to the current ad hoc and unprecedented monetary policies of global central banks. Personally I assign zero probability to this as it would entail quick economic depression for so many economies. But that does not mean gold does not have a purpose.

Others have purchased gold convinced the US and other major economies are soon to embark on an inflationary spiral, with hyperinflation a possibility due to the magnitude of printed money in the current cycle. So far, that inflationary cycle has remained elusive as deflationary forces inherent in a debt deleveraging cycle have offset central banker otherwise inflationary actions. But that does not mean gold does not have a purpose.

Others have purchased gold, especially in the post 2008 period, as a “tail risk” hedge against broader financial markets. As you may remember from your college statistics class, the “tails” of the normal distribution curve, or bell curve, are areas of very low probability outcomes. In the financial markets, an example of a “tail risk” is a market crash. It’s just not something that happens frequently (although when one does occur, it’s not easily forgotten). After what occurred in the equity and credit markets from mid-2007 through early 2009, it’s only a natural that investors then incorporated some type of tail risk protection into portfolios. Now that equity and credit markets are back to all-time highs, with promises by the world’s top central banks to do “whatever it takes” by printing money to support economies and financial markets, the perception is that “tail risk” is much less of a threat than over the prior four years – or perhaps not a threat at all. Hence, there is the perception of a lessened need for gold in portfolios as financial disaster insurance. But that does not mean that gold does not have a purpose.

And still others have purchased gold as a hedge against systemic risk. We can all remember clearly the final days of 2008 and early days of 2009. Questions regarding the viability of the US banking system were very real. Fast forward to the present and the Fed has largely engineered the recapitalization of the US banking system via bond purchases, allowing the banks to earn an interest spread between the cost and use of their funds, clearly at the expense of depositors. For now, US banking/financial system systemic risk is off the table in the US. But that does not mean gold does not have a purpose.

So, are these the answers to the question, “What’s wrong with gold”? And if so, is it true that the gold bull market begun at the dawn of the last decade is over?

We need to remember that everything talked about above can be considered an abnormal, or “crisis” type of event (tail risk, systemic risk, etc.). Think back to the late 1970’s when US inflation was in double digit territory and gold was soaring. Investors at the time had never seen inflation rates like that. A crisis due to generational highs in inflationary expectations and real price pressures? Gold responded. Was Nixon taking the US off the gold standard in the early 1970’s a crisis? It may not have been seen as one at the time, but what followed was a drumbeat of successive country currency crises over the ensuing decade’s right up to the present. Gold responded.

In my mind, what’s wrong with gold is first that investor perceptions of a crisis probability is now low. Consider that this is a perception susceptible to change. The financial markets are characterized by changing investor “focal points”, or perceptions, over time. I’m convinced change in risk perception is short term, and has occurred due to unprecedented global central bank actions over the last 6-9 months. The consensus is that so long as the global central bankers are printing unprecedented amounts of money, the financial markets, banking systems and general economies are safe.

So where does this leave gold? My suggestion is that looking forward gold will now be much more of a barometer concerning confidence in central bank and political decision making – that’s its current purpose.

Prior to this year’s gold price correction, I sold half of the gold exposure in client accounts after holding positions for over a decade, in part due to the short term perceptual issues I discussed above. I remain convinced financial markets in 2013 are being driven by the weight and movement of global capital, specifically scared Yen and Euro capital moving into dollar denominated assets. When this occurs, the dollar strengths and the Euro and the Yen weaken. The rise in the Japanese Nikkei this year has much more to do with underweight global institutional investors jumping in. Domestic Japanese investors continue for now to invest outside of Japan. Global currency movements can also impact the price of gold over the short term. Historically, gold prices have moved inversely with the dollar. As global capital concentrates in the US dollar, the dollar rises in value. Again, history tells us a rising dollar is not a gold friendly environment, another part of the rationale for lightening up now.

Secondly, headline inflationary stats have been receding. Historically, gold has performed very well in a “negative real interest rate” environment. In English, that means interest rates below the rate of inflation. This year interest rates have held steady while short term inflation rates have fallen – in other words “real” interest rates have actually become “less negative”. Very short term, that’s less of a support for gold prices. Lastly, it was simply the realization that in any long term asset class bull market, assets need time to rest and time to consolidate before again moving higher. It’s simply time for gold to rest. So, is the more than decade long bull market in gold over? Although it’s mandatory to monitor as we move ahead, I’d suggest to you it’s not over by a long shot. Why?

The gold bull market being over would mean that central bank and political decision making ahead will be mistake free. That they’ll lead us all to the land of sustainable economic expansion with nary a bump in the road, and all prior issues related to global excess debt balances will be magically resolved to everyone’s benefit. If I truly believed that, I would have sold every ounce of gold we owned and be personally short gold. I’ve done neither, nor do I expect to any time soon.

What lies ahead that could potentially break investor confidence in central bankers/politicians, leading to a renewed attraction to gold as being a meaningful asset within a diversified portfolio?

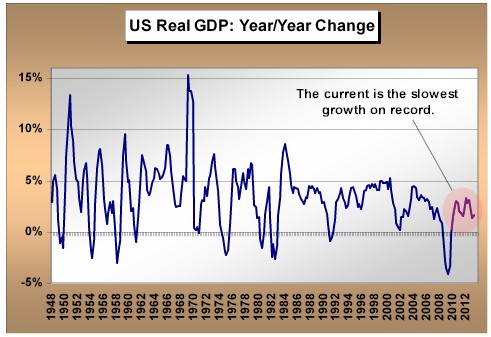

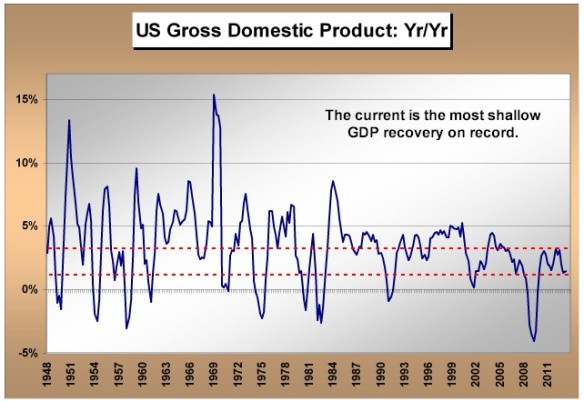

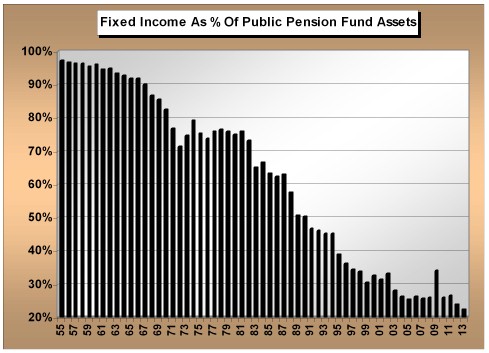

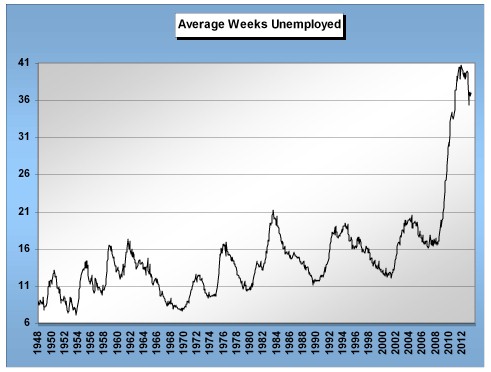

1) The US Fed has been printing money/expanding their balance sheet since early 2009. Since then they have printed close to $2.5 trillion. Since 2007, central bankers collectively have printed over $11 trillion. Unfortunately these Herculean efforts have not driven large global economies back to GDP trend growth. Growth rates in the current cycle are running at half the average of 1940-2008. Will printing another $1 trillion annually change this? How will this differ from the first $2.5 trillion of monetary expansion? And if economies do not reaccelerate, then what?

2) The Japanese are now intent on printing money at a rate twice that of the US Fed. This after more than two decades of economic deflationary pressure despite many prior money printing exercises by the Bank of Japan. Will the Japanese economy positively respond with this recent and most forceful monetary iteration? Moreover, in a current world of very slow to no growth in aggregate demand, will economic success in Japan simply be borrowing growth from another country or series of countries, in essence a zero sum effect for the global economy? If so, then what do central bankers and politicians do next?

3) So far, major developed economies have chosen to print money as a prescription for slow economic growth. What has been avoided is meaningful systemic reform accompanying the remarkable monetary stimulus. The need for reform has not disappeared, only been deferred. In the US this includes honestly and proactively addressing debt, deficit and entitlement expansion. All meaningful focal points of real reform have eluded Europe, the US and Japan. A failure to accomplish true economic infrastructure reform will mean the global money printing is for naught. Will this essential reform be accomplished and when will it start in earnest? Put otherwise, if central banks print historic amounts of money, yet politicians fail to enact needed reforms, which will alienate part or all of their political voter base – then what?

Remember, financial markets are not driven by a consistent and unchanging set of factors over time. Investor focal points change. For now the key focal point upholding investor confidence is the unprecedented magnitude with which global central banks are printing money, accompanied by promises to do more. But the core issues mentioned above have not magically disappeared. It’s in the reality of structural reforms where the real economic rubber meets the road. For now, global central bankers are being given “the benefit of the doubt” that all will end well. The thinking is that nothing can go wrong as long as money printing is in force. But for gold, that’s only half the equation.

We all know money cannot be printed indefinitely (especially in the magnitudes we see today) without adverse consequences to both financial markets and real economies. The real risk ahead is that reforms addressing debt, deficits, entitlements, currency infrastructure, and systemic risks will never occur. These require strong and decisive political thinking that translates into direct action. That’s where the real risk comes into play.

IF unprecedented money printing is not accompanied by successful and sustainable economic reform in the major developed economies over the next 12-18 months, gold will respond. That’s the investment thesis for gold as we look over the next few years.

How far could the price of gold fall before the current correction reverses? As always, it’s anyone’s guess and depends heavily on supply and demand balances. Although global demand for physical gold has remained incredibly strong, it’s the paper markets where we see the weakness. Gold near 1100 is not out of the question before this correction ends. But given the politically tenuous prospect for global economic reforms accompanying monetary policy across the planet, we may be looking at the final third of the secular gold bull market perhaps beginning sometime later this year or into 2014. The central bankers and politicians have so far inspired short term confidence in the financial asset markets. It’s now up to these politicians and central bankers to address the tough reform issues. If they do not, gold will have a purpose.